Kepler Museum

This week we had a tour of Regensburg’s Johannes Kepler museum. He did not live in Regensburg, nor do his work here, but he had friends here and died while visiting them. So the city created a museum in part to honor his contributions to astronomy and (mostly) to preserve a fine example of a 13th century house. The museum has a number of early astronomic instruments none of which are of Kepler’s time, admitted our tour guide sheepishly, but of the 18th century. However the museum does hold Kepler notebooks and first editions.

This week we had a tour of Regensburg’s Johannes Kepler museum. He did not live in Regensburg, nor do his work here, but he had friends here and died while visiting them. So the city created a museum in part to honor his contributions to astronomy and (mostly) to preserve a fine example of a 13th century house. The museum has a number of early astronomic instruments none of which are of Kepler’s time, admitted our tour guide sheepishly, but of the 18th century. However the museum does hold Kepler notebooks and first editions.

One of the more interesting museum documents records the failure of a gathering of Catholic and Protestant scholars summoned by the Holy Roman Emperor at Regensburg to decide whether to continue to use venerable but less accurate Julian calendar or to accept Pope Gregory XIII’s. The latter was more was made more accurate by shaving10 days from the Julian date and by adjusting the reckoning of leap year. But the politics of religion trumped science. Protestants refused to accept the Pope’s calendar on the principle that the Pope could do no right. The document shown here, signed by Kepler in Regensburg, is an agreement to disagree.

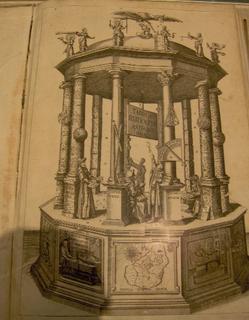

Kepler is sometimes called the “father of modern astronomy” for his discovery that the planets have elliptical orbits, traveling faster as they approach the sun, and for his “three laws” supporting his observation. The first two laws he published in Astronomia nova (1609) and the third ten years later in Harmonice mundi.

Kepler is sometimes called the “father of modern astronomy” for his discovery that the planets have elliptical orbits, traveling faster as they approach the sun, and for his “three laws” supporting his observation. The first two laws he published in Astronomia nova (1609) and the third ten years later in Harmonice mundi.He began his career as a professor of mathematics at the university in Graz, Austria where he wrote his Mysterium cosmographicum. Its publication led to correspondence with Galileo, a proponent of the Copernican solar system, and with Tycho Brahe, court astronomer to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. Kepler’s book led to his appointment as mathematician to Rudolf II’s court at Prague. Rudolf may or may not have been mentally unbalanced (as some histories say) but he was far more interested in art, music and science that in the affairs of empire which came to be conducted by his brother Matthias.

When Tycho died not long after Kepler’s arrival, Kepler took his place as court astronomer. Although Tycho rejected Copernican geocentric planetary system, his extensive records of planetary movements made at his Prague observatory, would provide the data for Kepler’s work. Kepler later published Tycho’s observations as Tabulae Rudolphinae, dedicated to Rudolf.

Our tour guide reported that Kepler found his position of astronomer was often confused with that of astrologer and he was often asked to do horoscopes and make predictions. Kepler thus took up the ancient art of astrology in which he did not believe. Nonetheless, some of his predictions were amazingly accurate as for instance his correct prediction of the day and year of the outbreak of the Thirty Years War.

Our tour guide reported that Kepler found his position of astronomer was often confused with that of astrologer and he was often asked to do horoscopes and make predictions. Kepler thus took up the ancient art of astrology in which he did not believe. Nonetheless, some of his predictions were amazingly accurate as for instance his correct prediction of the day and year of the outbreak of the Thirty Years War.

Historians of science have held Kepler as an example of the magic and mysticism that suffused the early sciences noting that, in his Harmonice mundi, he used the same mathematical calculations by which he demonstrated the elliptic of planetary orbits the increasing speed of their orbits as they approach the sun to hypothesized that planets had "songs" that increased in pitch as they near the sun. Kepler spoke of this as “God’s music.” Modern critics saw this as proof that while Kepler’s head may have been that of a modern, his feet were planted firmly in medieval superstition.

But was Kepler really wrong? If he was, what are astronomers doing with their hundreds of arrays of dish antennas—radio telescopes—tracking and recording sounds emitted by celestial bodies from pulsars to galaxies. Listening to God’s Music perhaps.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home