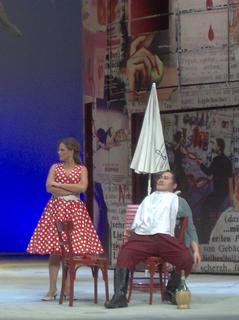

L'elisir d'amore--A Night at the Opera

A night at the opera for the crew. We attended a performance of The Elixir of Love at Der Kronleuchter, the Regensburg city theater. Initially some, including me, were not all that keen on the opera. I like every sort of music under the sun, but I’ve never liked opera which I associated with over-trained coloratura sopranos, the fat ladies who must sing (and sing and sing and sing) before IT’S OVER.

A night at the opera for the crew. We attended a performance of The Elixir of Love at Der Kronleuchter, the Regensburg city theater. Initially some, including me, were not all that keen on the opera. I like every sort of music under the sun, but I’ve never liked opera which I associated with over-trained coloratura sopranos, the fat ladies who must sing (and sing and sing and sing) before IT’S OVER.

But David convinced me that I couldn’t consider myself civilized until I saw an opera. Our students didn’t have to be convinced—they had to attend as part of their art history class, although to be fair, a number of them had already attended opera performances on their own. I guess I was really the uncivilized one.

But Domenico Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore (Milan premire, 1832) was an entertaining bit of Italian fluff without a fat lady in sight, well acted, well (not over) sung, closer to Broadway than Wagner. Well, the Italian libretto was sung in German, but the plot--a variation of the classic Boy meets girl. Boy loses girl. Boy gets girl--was not hard to follow although all the word-play was lost on me (Niki later told me the lyrics were quite funny).

Donizetti (1798--1848) was one of the most popular and prolific opera composers of his age. He is said to have composed over 70 operas but the exact number is unknown because many were lost after he went out of fashion. The year he died, however, one third of the Italian operas being performed were his. He was born poor but his talent was recognized and he was enrolled in a charity music academy along with his older brother (who went on to become the Instructor General of the Imperial Ottoman Music at the court of Sultan Mahmud II—now THAT would make a great opera). Donizetti is credited as the father of Italian comic opera who inspired Verdi and Arthur Sullivan of Gilbert and Sullivan.

Synopsis of The Elixir of Love (premire Milan, 1832)

taken from http://www.operatampa.org/season/elixirsynopsis.htm

ACT I

ACT IAdina, wealthy owner of a local farm, her friend Giannetta and a group of peasants are resting beneath a shade tree on her estate. From a distance, Nemorino, a young villager, watches the bucolic scene, lamenting that he has nothing to offer Adina but love (“Quanto è bella”). The peasants urge their mistress to read them a story — how Tristan won the heart of Isolde by drinking a magic love potion (“Della crudele Isotta”). No sooner has she done so than Sgt. Belcore swaggers in with his troop (“Or se m"ami”).

The soldier’s conceit amuses Adina, but he is not dissuaded from asking her hand in marriage. Promising to think the offer over, she orders refreshments for his comrades. When Adina and Nemorino are left alone, she tells him his time would be better spent looking after his ailing uncle than mooning over her, for she is fickle as a breeze (“Chiedi all’aura lusinghiera”).

The soldier’s conceit amuses Adina, but he is not dissuaded from asking her hand in marriage. Promising to think the offer over, she orders refreshments for his comrades. When Adina and Nemorino are left alone, she tells him his time would be better spent looking after his ailing uncle than mooning over her, for she is fickle as a breeze (“Chiedi all’aura lusinghiera”). In the town piazza, villagers hail Dr. Dulcamara, who enters in a magnificent carriage that proclaims the patent medicine he is selling. The quack declares the potion capable of curing anything (“Udite, o rustici!”). Since it is inexpensive, the villagers buy eagerly. When they have gone, Nemorino asks Dulcamara if he sells the elixir of love described in Adina’s book (“Avreste voi per caso”).

Pulling out a bottle of Bordeaux, the charlatan declares this is the very draught. Though it costs him his last cent, Nemorino buys the wine and hastily drinks it. Adina enters to find him tipsy; certain he will win her love, he pretends indifference (“Esulti pur la barbara”). To punish him, Adina flirts with Belcore, who, informed that he must return to his garrison, persuades her to marry him at once. Horrified, Nemorino begs Adina to wait one more day (“Adina, credimi”), but she ignores him and invites the entire village to her wedding feast. As the peasants shout taunts (“Vedete un po’”), Nemorino rushes away, moaning that he has been ruined by Dulcamara’s elixir.

ACT II

At a local tavern, the pre-wedding supper is in progress (“Cantiamo, facciam brindisi”). Dulcamara, self-appointed master of ceremonies, sits with the bridal couple. “What a pity Nemorino cannot see how happy we are,” thinks Adina. Her mind is distracted by the doctor, who suggests they blend their voices in a barcarole about a gondoliera and her wealthy suitor (“Io son ricco”). When the duet ends, Adina goes off with Belcore to sign the marriage contract; the guests disperse. Remaining behind, Dulcamara is joined by Nemorino, who begs for another bottle of elixir; his pleas are rejected because of lack of funds.

Belcore returns, annoyed because Adina has postponed the wedding until nightfall; when he spies Nemorino, he asks why the youth is so sad. Nemorino explains his financial plight, whereupon the sergeant persuades him to join the army to receive a bonus awaiting all volunteers (“Venti scudi”). Belcore leads the perplexed Nemorino off to sign him up, enabling him to buy more elixir.

Peasant girls, gathered in the square, learn from Giannetta that Nemorino’s uncle has died and willed him a fortune (“Possibilissimo. Non è probabile!”). When he reels in, giddy from a second bottle of wine, they besiege him with attention; unaware of his new wealth, he believes the elixir finally has taken effect (“Dell’elisir mirabile”). Adina and Dulcamara arrive in time to see him leave with a bevy of beauties, and she, angry that he has sold his freedom to Belcore, grows doubly furious (“Quanto amore! ed io spietata”).

Scenting a new sale, Dulcamara claims that Nemorino’s popularity is due to the magic elixir. Adina replies that she will win him back through feminine charms. Reentering alone in a pensive mood, Nemorino takes heart because of a tear he has seen on Adina’s cheek (“Una furtiva lagrima”), but when she appears, he acts disinterested. She confesses she bought back his enlistment papers because she loves him (“Prendi, per me sei libero”).

Back in the piazza, Belcore marches in to find Adina affianced to Nemorino; declaring that thousands of women await him, he accepts the situation philosophically. Attributing Nemorino’s happiness and inheritance to the elixir, Dulcamara quickly sells more bottles before making his escape (“Ei corregge ogni diffetto”).

This was disputed by those who believed in a Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Spirit as one). Arianism was declared heresy in 325 at the First Council of Nicaea but it took many centuries before it could be rooted out, especially among the Germanic tribes where it had been spread by pious Arian missionaries.

This was disputed by those who believed in a Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Spirit as one). Arianism was declared heresy in 325 at the First Council of Nicaea but it took many centuries before it could be rooted out, especially among the Germanic tribes where it had been spread by pious Arian missionaries.

The rest comes from the Catholic Encyclopedia:

The rest comes from the Catholic Encyclopedia:  It was still further enlarged by Charlemagne about the year 800 and endowed with extensive possessions and many privileges. When St. Boniface, in 739, divided Bavaria into four diocese, the first Bishop of Ratisbon fixed his see at the Abbey of St. Emmeram, but later on it was removed by a subsequent bishop to the old Cathedral of St. Stephen, which stands beside the present one.

It was still further enlarged by Charlemagne about the year 800 and endowed with extensive possessions and many privileges. When St. Boniface, in 739, divided Bavaria into four diocese, the first Bishop of Ratisbon fixed his see at the Abbey of St. Emmeram, but later on it was removed by a subsequent bishop to the old Cathedral of St. Stephen, which stands beside the present one.

I was impressed by bass player as well, who never got a solo break (at least while I was there) but whose lines were fluid and melodic. As a former jazz bassist, I appreciate lines that don’t stay with tonic, third, fourth, fifth. I listened to the trio for 45 minutes, then, forgetting about the park, went to buy some groceries. They were still there when I came back by and I listened another 20 minutes or so.

I was impressed by bass player as well, who never got a solo break (at least while I was there) but whose lines were fluid and melodic. As a former jazz bassist, I appreciate lines that don’t stay with tonic, third, fourth, fifth. I listened to the trio for 45 minutes, then, forgetting about the park, went to buy some groceries. They were still there when I came back by and I listened another 20 minutes or so.

Jacobowitz has written book of his experiences A Classical Klezmer: Travel Stories of a Jewish Musician some of which may be read in full text on his website.

Jacobowitz has written book of his experiences A Classical Klezmer: Travel Stories of a Jewish Musician some of which may be read in full text on his website.

On an impluse, I copied the words to Adieu, sweet lovely Nancy and returned to the street. Brigitte had changed locations and was playing at the Alter Korn Market. She smiled when she saw me and I sat down in a sunny place and listened. And as I followed her around for the rest of the day, I learned a few things about the life of a street musician. Street performers must have a license to play for money and the police did check to insure she was licensed and playing in the areas assigned her. Street musicians can play only 30-45 minutes in one location and it is illegal to play between the hours of one and three.

On an impluse, I copied the words to Adieu, sweet lovely Nancy and returned to the street. Brigitte had changed locations and was playing at the Alter Korn Market. She smiled when she saw me and I sat down in a sunny place and listened. And as I followed her around for the rest of the day, I learned a few things about the life of a street musician. Street performers must have a license to play for money and the police did check to insure she was licensed and playing in the areas assigned her. Street musicians can play only 30-45 minutes in one location and it is illegal to play between the hours of one and three.

Brigitte plays once a week in Regensburg. Stop, listen and show your appreciation.

Brigitte plays once a week in Regensburg. Stop, listen and show your appreciation.

This afternoon on our tour of the Jewish archeological site at Neupfarrplatz we were joined by Professor of Marketing Fred Miller who chairs Regensburg Programs Committee.

This afternoon on our tour of the Jewish archeological site at Neupfarrplatz we were joined by Professor of Marketing Fred Miller who chairs Regensburg Programs Committee.